Thursday, March 12, 2009

The herring, the Chinook and the orca...At the Brink

By BRIONY PENN from the March 2009 Focus Magazine

All sorts of creatures want to eat the oily, life-giving Pacific herring, but the little fish is getting harder to find in the Salish Sea. Amongst those having to make do with less are Chinook salmon, whose numbers are also in sharp decline. And, in the last decade, the number of resident orca in the Strait of Georgia-who largely depend on a diet of Chinook salmon-dropped from 97 to 83. The health of these three species may be closely linked, or the linkage may be an old fishers' tale. Nobody seems to know for certain. And yet Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) continue to allow a herring roe fishery each Spring-12,000 tons this year-in which female herring are stripped of their roe (which is shipped to Japan and sold as a luxury food) and then ground up with the males for use as fish meal.

Just over a decade ago this March, a busload of British tourists taking in the sights of Chemainus were interrupted by a noisy demonstration. A group of fishers, naturalists, First Nations people, Gulf Islanders, environmentalists and ecotourism providers from around the Salish Sea marched down the main street of the town with big banners that said "Save the Herring."

Unbeknownst to the tourists, the protesters were wrapping up an island-wide protest that had charted a course from one depleted traditional herring spawning ground to another, ending up near the Chemainus spawning site. I was one of the protesters and was carrying a sign on which I had painted an orca eating aChinook salmon that was eating a herring- a basic food chain for the region that you learn about in island schools around Grade 4.

As I marched down the street with my sign, a British woman cried out, "'Why do you want to save the 'erring? I 'ated eatin' 'erring." I pointed to my sign earnestly. "We want to save the herring for everything else that does like eating herring. Like whales." The woman agreed that she liked whales-and could she buy my sign for a souvenir?

There are three purposes to this story.

First, it demonstrates that people have been worried about the herring populations on the coast for a while. You don't match around Chemainus with signs saying "Save the Herring" without already having exhausted a lot of other options.

Second, it demonstrates protesters' concerns were valid. Nobody from the fishers to scientists ever questioned the food chain that I had painted on my sign that Chinook eat herring and resident orcas eat Chinook. A decade ago, there were 97 southern resident orca; now their population is 83. There used to be lots of local herring populations on the coast that people and wildlife relied on in more ways than one. The protesters were all local people raising the alarm of a silent spring in their respective bays-a silent spring which has spread to more bays since.

The story also hints at the reality, that there is more money to be made in live wildlife than dead. The British wiped out their herring industry and all their wildlife, so now they holiday in Canada and will even go to the length of buying a protester's sign to prove that they were in the land of the whales.

To experience a herring spawn is to behold one of the natural wonders of the world-the reek of the roe, the roar of the sea lions, the raucous gulls, the thrashing frenzy of millions of herring, the furious splashing of the salmon and seals. Bays turn milky blue with the milt (spawn) and vast rafts of seabirds, black and white against the grey water, hover offshore waiting to feast on the roe. It is March's answer to winter's mal de vivre. But for many of us watching from the shorelines lately, it has been another silent spring.

Herring are nature's nutritional wonder food. They fatten up the food chain so that everything can go off and breed-harlequin ducks, scoters, goldeneye, western grebes, herons, marbled murrelets, coho and Chinook salmon, lingcod, rockfish, humpback and minke whale all benefit firsthand (and the orca via the Chinook) from the rich injection of energy into the system at a much-needed time in the early spring.

These species and their habitat are already under stress from many factors-warming waters, changing acidity, hardening of the shoreline from urbanization, aquaculture, destruction of eelgrass beds, chemical toxins, changes in predator patterns, invasive species and increased shipping and boat traffic, to name a few. The protesters felt and many experts agree that, at the very least, we should leave their food source alone. With full stomachs of herring, the wildlife of the coast might be able to weather all the other stresses thrown at them.

Herring history

Between'1940 and 1968, fishers on the coast engaged in what was called the herring reduction fishery-the first bonanza years. Hundreds of thousands of tonnes of herring were caught and "reduced" down to oil and fish meal. When the herring population collapsed, the fishery was closed.

It opened up again under another name, the "roe herring fishery," as population numbers inched back up. When I was 16 in 1976, the fishery was back in full swing. I know because I worked in a roe herring factory. Twelve hours a day, I stripped roe from the females and threw the rest of the catch on the ground where, at the end of the day, the carcasses, thigh deep, were swept up for fish meal. That bonanza petered out a few years later, only to rise again under a new, more conservative management regime.

Today, the roe herring fishery is dominated by the herring seine fleet, which fishes first and takes the biggest slice. It is entirely owned by BC billionaire Jimmy Pattison's Canadian Fishing Company (Canfisco). Pacific herring are harvested mainly for their roe; Canfisco's golden herring roe is shipped primarily to Japan. The carcasses of herring left over after roe removal are reduced into fertilizer and animal feed.

The gillnetters, which fish selectively for larger fish, take a smaller, later cut, and the herring that are left to spawn provide the basis for a First Nations "roe on kelp" fishery, a traditional form of harvesting where the eggs are harvested once they have been laid on the kelp. In the roe on kelp fishery, no fish die and just a proportion of the roe is harvested.

In the winter, two small but controversial fisheries have been created that target resident populations of herring: the winter food and bait fishery, and the sports bait fishery.

Ten years ago, environmentalists, such as those at the above-mentioned protest, urged the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to adopt a forage fish policy along the lines of that of Washington State. Forage fish are food for other fish and wildlife. A forage fish policy recognizes the needs of salmon, lingcod and other wildlife, before allocating any commercial harvesting. It was also suggested the herring fishery be closed down for a period of time to assess stocks and wildlife needs.

David Ellis, ex-salmon fisher, First Nations consultant, past head of Pacific Region Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, and long-time activist with Fish for Life, had proposed that fishers or companies in Canada hold catch insurance policies, like farmers' crop insurance, so they wouldn't be pressured to fish when stocks were low. If populations didn't recover, then at least we didn’t have our fishery to blame.

The situation today

There is still no forage fish policy in Canada.

Jake Schweigert, called “the herring guy" at DFO, has been looking at herring for 30 years. He predicts herring populations by looking at information from the annual catch since 1950-age and weight, total area and intensity of the herring spawn-and plugging

it into models. Schweigert maintains that DFO has taken a precautionary approach since the bad old days of the herring reduction fishery. Today they only catch a maximum of 20 percent of his forecasts for the population. If the forecast is below the "cutoff " level, the fishery is closed. Cutoff is set at a quarter of the average estimated population, assuming that there was no fishing.

But many are not happy with DFO's approach. As a reporter, I've covered protests against the continuing herring fishery in the Strait of Georgia, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, on the central coast, and the Queen Charlotte Islands. One protest, near Bella Bella, involved a big seine boat owned by Canfisco homing in on a large ball of herring and encircling it in its seine nets. Seabirds, sea lions, and locals in boats with banners flying were snapping, screaming and roaring around the nets filled with undersized silver herring flipping and dazed as they were raised onto the seiner. The protesters were Heiltsuk fishers who relied on the roe on kelp fishery, a fishery used to support 600 people in Bella Bella.

Harvey Humchitt, fisher and hereditary chef of the Heiltsuk Nation, was steering one of the boats at that protest. He was watching a way of life disappearing into those nets. "If we lose the herring, we lose salmon, seals, whales, everything." Humchitt reels off a list of problems with the fishery, from the method of predicting to the reporting of catch.

The herring forecast for the central coast this year is, like last year, nearly 12,000 tons below the cutoff level of 17,600 tons. As a result, no harvest is recommended including the spawn on kelp.

Stocks have also declined below their cutoff level on the west coast of Vancouver Island and the Queen Charlotte Islands. There will be more hungry Chinook, more hungry whales and more hungry communities. The DFO graph of herring population over time for the Strait of Georgia suggests the fishery here is headed in the same direction as the central coast's. It shows a precipitous decline, and although it isn't at the cutoff level it is very close. Yet 12,000 tons of herring are due for removal from around the Salish Sea this month (February 2009).

Theories on the disappearing herring

The health of these stocks have always generated a lot of debate and confusion. Part of the difficulty stems from the fact that herring behave a bit like orcas: there are resident stocks and migratory stocks. Migratory herring come in to breed from the western shelf of Vancouver Island and leave again after they reach one or two years old. Unlike orcas, however, it is hard to tell the difference, and there is disagreement about whether there are distinct stocks, even among fish geneticists.

What we do know is that small resident populations up and down the island are flickering out. On the other hand, big migratory spawning populations recorded historic highs in places like Hornby/Denman Islands in the early 2000s, leading some to believe herring were in good shape.

Protecting the Saltspring Island herring in the Fulford and Ganges spawning grounds was one of the main reasons that drove me to protest in the streets of Chemainus ten years ago. Saltspring herring were renowned for being the first of the season to spawn. Early spring in mv harbour used to be heralded by balls of herring-the bay turning milky blue with the spawn-and a cacophony of birds and marine mammals. But there hadn't been a noticeable spawn there for a decade, and just when numbers might have been starting to rebuild, DFO opened up the fishery again because the Strait of Georgia gillnet roe herring fishery couldn't meet their quota in the Hornby/Denman area- the fish were too small and were swimming through their nets.

According to David Ellis, "The importance of maintaining the full diversity of local and migratory stocks has been underrated because it doesn't suit the business model and we defend the business world at all costs first." Fred Felleman, marine biologist and consultant for Friends of the Earth, shared similar sentiments from his office on the US side of the Salish Sea: "The tragedy is that they are being treated as one stock. It is biologically bankrupt to treat the population as a metapopulation. Yet, while some biologists like Felleman identify the Cherry Point (Puget Sound) population as genetically distinct, others don't think this warrants special status. Felleman also told me, "We tried to have them listed as an endangered species, but with refineries sharing their spawning grounds, this hasn't been an easy sell."

Back in Canada, DFO's Schweigert allows that food and bait fisheries in the 80s might have been a factor in reducing local resident populations, but that a one-degree temperature increase in the Strait of Georgia waters is probably more to blame than a fishery.

David Ellis is not convinced. He feels that blaming warning temperatures (used back in 1968, as well) is a red herring, since herring are traditionally found as far south as California. Nor does it explain changes up north. In Alaska, the same pattern has been occurring and citizens' action groups have formed with the same concerns and observations as in BC.

Doug Hay, retired herring biologist for DFO, acknowledges that the question of genetic distinctiveness is also a bit of a red herring. "There are undoubtedly resident populations and they have suffered. The question, though, is why have some resident populations disappeared, like Boundary Bay, when we never had a fishery there?”

Traditional wisdom, as shared by Chief Humchitt, says there is an answer to that question. "We started noticing a decline in all our small spawning areas years ago and tried to bring attention to DFO not to fish in what we call the herring gathering or staging areas, such as Spiller Channel [near Bella Bella]. Traditionally, we never fished Spiller because the fish would gather there before dispersing to spawn in all our little bays." Humchitt reels off a dozen spawning grounds that have gone. "They ignored our advice not to fish Spiller, and fished it really heavily even when we pointed out that 60 percent of our spawning grounds had gone. We wanted to preserve our stocks; that was why we protested, year after year. But they never wanted to listen to our local knowledge. And now the herring stocks are pretty much gone."

Hay agrees that Humchitt has a legitimate concern. "We know there are these [what he calls] over-wintering areas, but we have noticed that they change over time." A much greater concern than the herring roe fishery, says Hay, is the industrialization of the coast, such as the development of the Bowser Bay scallop aquaculture industry located in the heart of "the most significant herring spawn location in BC." In a letter to the former provincial Minister of Agriculture and Lands, Pat Bell, Hay urged Bell to “take steps to limit future industrialization of the Bowser area coastal zone, and adjacent areas. These areas support very important herring habitat."

The links: herring, Chinook, orca

To get inside a herring researcher's brain, and indeed a herring brain, you have to understand what constraints a herring is working under. Everything wants to eat you. There is some safety in numbers. Yet, the odd loners often become the sexually fittest because they dodge the predators, including nets, by going somewhere different to spawn and outwitting fishermen.

For spawning to be successful, however, a lot of herring are needed because the milt is released into the bay and if the bay doesn't turn milky white, the chance of fertilisation is reduced.

For the species to have survived this long, it must have developed the most extraordinary survival tactics, including subpopulations that spawned at different times, different temperatures, different salinities and different currents.

We know herring vary over time and we know that we are in the midst of enormous environmental shifts. According to Hay, we also know that in the last 25 years the traditional 200 spawning grounds in the Salish Sea have declined drastically. But in spite of these declines this year's herring quota of 12,000 tons-59,000 tons of total biomass are predicted-is exactly the same as it was a decade ago when there was twice the biomass of herring and 97 orcas to feed.

Which brings us to the link between the declining orca numbers and the collapsing Chinook populations. Jake Schweigert says there is no data for that correlation. "During the herring reduction years when the fishery really did put pressure on the herring stocks, there was no associated Chinook collapse." But David Ellis cites studies on Chinook diets by DFO scientists (Pritchard and Tester, 1944) that clearly show that herring-or pilchard when available-form a high proportion of the Chinook's diet-46 percent in some years. Any fisherman will tell you, says Ellis, to throw out a herring-mimicking buzzbomb to catch Chinook, "Everything we say is written off as old fishermen's tales."

I asked Schweigert whether there were any long-term studies done on the diet of Chinook and these linkages, or whether studies have been proposed in light of these drastic declines. The answer was "no" on both counts. It seems we have to rely on data from our neighbours across the water who have listed the Puget Sound Chinook as a threatened species. In a November article in the Seattle Times, US officials acknowledged the need to rebuild species the Chinook depend on, like the Cherry Point herring stocks.

And what of the whales? The "whale guy" in BC is Graeme Ellis (no relation to David Ellis), with the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, who has been observing orcas since he worked as a whale trainer in the 60s. Ellis doesn't deny the link between declining herring, Chinook and hungry whales, but says, "I don't think we understand how complex these relationships can be."

Ellis does the inventory of southern resident orcas in the Strait of Georgia each year. With seven animals reported missing, there was a lot of concern and speculation about the causes. A terrible return of Chinook was identified as one of the factors. Ellis was cautious about putting too much emphasis on the deaths, as only two of those were "not expected” in the usual demographics of a population. "But we need to pay attention if we continue to get unusual mortality events."

With regard to the herring issue, Ellis says, "There are people scratching their heads wondering why herring are disappearing even where there are no fisheries. The 2005 year class had a terrible year with warm ocean temperatures, which had an impact on both Chinook and herring. It is death by a thousand cuts for so many species. The causes of population declines may be anything and everything from climate change, habitat degradation including the effluents we are putting down our drains, and the hardening of the shoreline, to past poor management practices, but I think we are all to blame." From Graeme Ellis' perspective, we should be "giving these forage fish a high importance and managing people's expectations about what we can take and better understand what the requirements of other species are."

Across the sea, whale researcher Sam Wasser, from University of Washington Centre for Conservation Biology, has been looking at killer whale survivorship and trying to separate out nutritional impacts from boat disturbance impacts by measuring thyroid hormone and cortisol levels in killer whale scat. Using his celebrated sniffer dog to sniff out whale scat, Wasser published the results this winter. "What we got was a strong nutritional signal tied to Chinook availability, with boat stress compounding it." He also notes that once the hungry whales start burning fat, which is where the toxins are stored, the toxins will weaken them further.

As biologist Felleman told me, "We can't just say save the whales, we have to save the Chinook, and the food for the Chinook. Otherwise we are really fooling ourselves that we can save the Sound.'

Heel dragging on herring protection

My last phone call was to the very man who benefits most from keeping the fishery open-Jimmy Pattison. The Jimmy Pattison Food Group owns Canfisco, which bills itself as "Canada's largest producer of wild salmon and herring roe." Pattison spends time cruising, the coast in his 150-foot yacht, Nova Spirit, no doubt enjoying the wildlife along the way. Who better to ask about herring than the man at the very top of the food chain ?

I got as far as his secretary. This was our Monty Pythonesque conversation. "Hello, I

would like to speak to Mr Pattison." "What about?" "Herring." "Herring? What does Mr Pattison have to do with herring?" “His company catches them." “Well then you'll have talk to the company CEO." "But I'd like to speak to Mr Pattison personally about the impacts of the herring industry; I assume he is a salmon fisherman as I see him up the coast every summer on his boat." "Mr Pattison doesn't fish." "But I'm sure he enjoys the wildlife that like herring." There is silence. "Mr Pattison will not be able to talk to you about herring."

In 1997, David Ellis had a similar experience with Pattison's secretary, so he wrote an open letter in which he asked Pattison to tie up his seine boats and work on conserving the herring stock. "At this time it is within your power to advocate changes that will serve your business interests in this fishery, and also serve the public interest in terms of the conservation of the fishes, birds and mammals of the Strait of Georgia."

Pattison never responded. Ellis tried again in 2003 with a media campaign recommending that we use precautionary harvest strategies that recognize the critical importance of herring spawn on kelp fisheries to the financial wellbeing of many coastal aboriginal communities.

He suggested to government that rebuilding programs for such species as lingcod, rockfish, coho and Chinook salmon, and killer whales, would have little credibility unless they included a comprehensive rebuilding program for the many depleted herring spawning sites in the Strait of Georgia. "Included in the equation must be the potential economic value to the Province of rebuilt bird watching, sporting fishing and whale watching industries, all of which are now clearly suffering heavy economic losses due to the continuance of large-scale roe herring fishing in the Strait," wrote Ellis. "We also need to factor in the improved quality of life of local citizens, who will enjoy higher local abundances of mammals, birds, and fishes."

There was a promise from DFO at the time to look at a forage fish policy, but it was never implemented. Doug Hay, the herring fishery biologist then, felt that the herring roe fishery was not the problem. “The impact of the herring roe fishery is small because the fishery is conservative, provided that they follow the guidelines. It has weaknesses and it is not as selective as I would like, but there are other bigger problems out there that we should be addressing." David Ellis points to a reduction in the mesh size of the nets as one example of how the guidelines have been weakened.

This month, as mentioned, 12,000 tons of herring will be harvested from nearby seas, mostly for Japanese roe-eaters. I imagine the Chinook might think this is a shameful, wasteful use of the little fish.

And the orcas too. As I write, it is dusk and eight orca are feeding off the point near where I live. Their exhalations and fluke slaps, on this calm February nigh, are like the sweetest symphony on Earth. Perhaps they are coming to feed on some Chinook drawn to the handful of herrings still remaining.

I know that I'm part of the problem; I paid my first year university tuition on the backs of dead herring. My Japanese bosses had come to BC because they fished their own herring grounds into extinction. We have hindsight now. So this is my open letter to all Of us who have it in our power to influence the wellbeing of this priceless gift. Please listen to the expert voices of people who know and love the coast. just do whatever is in your control to help the herring.

Briony Penn PhD (Geography) is a naturalist, journalist and artist with deep roots on BC’s coast. She is the author of The Kids Book of Geography (Kids Can Press) and A Year on the Wild Side. This article was originally publish in Focus Magazine, March 2009 issue, pages 24-29

Sunday, February 1, 2009

Forage Fish of Metchosin

FORAGE FISH OF METCHOSIN

By Moralea Milne for January 2009 Metchosin Muse

Dec 13, 2008

If you take a walk along Taylor Beach you will often see river otters chasing each other through the waves and curious seals stare at you with their velvet painting eyes. Sea birds whirl and alight in the choppy grey sea. These animals provide some visual reference to the surrounding waters but the marine world is not one that is easily accessible to terrestrial creatures such as ourselves.

Just off the beach are large eelgrass beds and seaweed communities that provide crucial nursery habitat for juvenile fish, crabs and octopus. Under our feet as we walk on the beach, Pacific sand lance and (possibly) surf smelts lay their eggs in the high intertidal zone, forgoing their usual aquatic environment during their incubation.

They are known as forage fish, the cornerstone of the nearshore food web that supplies a critical food resource to commercial species such as salmon and cutthroat trout. Seals, sea lions, whales and seabirds, comprise part of the 100 species that are dependant on forage fish for their survival. A 2007 report states that “thirty five percent of the diet of juvenile salmon and sixty percent of the diet of Chinook salmon are comprised of Pacific sand lance”. Because they forage close to the shoreline, coastal cutthroat trout are heavily dependant on sand lance and surf smelts; fifty percent of our endangered humpback whales’ diets are sand lance. Marine birds are also dependant on these fish, there are estimations that seventy five percent of rhinocerous auklet’s food intake and fifty percent of the endangered marbeled murrelet’s diet are comprised of forage fish. Forage fish include Pacific herring, sardines, capelin, eulachon and northern anchovy as well as Pacific sand lance (aka needlefish) and surf smelts.

At night, Pacific sand lance (Ammodytes hexapterus) burrow in the sand as a means of escaping predators, sometimes surprising people walking at low tide along a beach, as they wriggle up from their nighttime “safe houses”. Some people will recognize them from the large, dense schools they form near the surface that are called “bait balls”. They spawn between November and February, more frequently in the late fall. Sand lance use their bodies to form small, shallow pits in sandy beaches, much like salmon redds, in which to deposit their spawn, which will hatch in four to five weeks. Both sand lance and surf smelts spawn during high tides, the upper beach must be covered in shallow water to facilitate egg deposition.

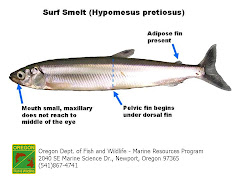

Surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus) can spawn at any time of the year, depending on weather, vegetation and probably many factors of which we are not aware. Surf smelt lay their sticky eggs in the high intertidal zone of a sand and gravel beach, just below the log line, usually between the two lines of deposited seaweed that are readily visible. Pea gravel sized stones, intermixed with coarse sand are preferred spawning material. Surf smelts who spawn in the summer make use of beaches with overhanging vegetation or areas with a continual underground movement of water (such as from a blocked stream slowly seeping through sand and gravel beds). These components ensure the smelt eggs will remain moist and viable under the hot summer conditions. Summer incubation and hatching happen within two weeks while cold winter conditions will increase the incubation time to one to two months. Surf smelt eggs can be found in small patches or they might cover miles of beach, depending on beach conditions and surf smelt abundance.

In order to ensure continued habitat for these important fish, it is important to understand how beaches are formed and maintained.

Bluffs and beaches form a type of unwitting partnership. The bluffs are subject to erosion because of their steepness, the type of material from which they are formed (clay, sand, gravel) and the force of wave action and storm events. Waves are powerful forces that continually act on shoreline materials. They pound against a bluff until it is undercut, when it will fall onto the shore, giving short term protection to the bluff. Slowly, wave action will distribute the fallen material, according to tides, currents and topography. The accumulation of these sediments on beaches and in shallow tidal ecosystems, provides habitat for many different species. Stormwater runoff and removal of bluff vegetation (especially to accommodate the desire for views), can dramatically increase the rate of erosion along bluffs.

Other creatures benefit from this eternal process. Under the cobbles of the low intertidal zone, in the area that is exposed only at low tides (visit the western end of Taylor Beach), you will find small squirming black eel-like creatures known as blennies. There are many species of blennies, some of which will lay their eggs under these cobbles. One or both of the parents will often remain to guard their developing young. At low tides, garter snakes and raccoons will descend from their land based territories and forage for blennies and other marine creatures. If you go searching for blennies, please respect their needs; lift the cobbles carefully and return them to their same positions.

It is not only the changes to rivers through logging activities, overharvesting and pollution from industrial and sewage contamination that has affected our declining marine stocks. Developments along shorelines, where we have not realized the cumulative effects of shoreline changes, have impacted heavily on the ability of marine species to survive. The bluffs to the west of Witty’s Lagoon are continually eroding and supplying sand to Witty’s beach. If you were to “harden” this area by erecting a wall to try to protect those slopes, you would eventually lose the beach.

A consequence of hardening shorelines, by building seawalls and other fortifications, is that the waves will now pound the adjacent shorelines with more force, causing a chain reaction of property owners hardening shorelines; the beaches that remain are scoured by the extra forces working on them and lose the soft sand and gravel that provide surf smelt and sand lance spawning habitat. Less spawning habitat = less forage fish = less food for the 100 species that feed on them.

If you have ever strolled the seawall around Stanley Park, or taken a boat cruise around Victoria’s shoreline, you will soon see that the beaches have been heavily impacted. Many of them have disappeared entirely or the high intertidal zones are gone or have been heavily scoured so that no spawning habitat remains. We are fortunate in that Metchosin has retained much of its forty-five kms of shoreline in relatively natural condition.

There are new “soft” techniques that have been developed to protect shoreline properties. Building natural formations such as sand and gravel berms, planting them with native shoreline grasses and trees, the placement of drift logs, all these mimic the natural barriers to erosion and contribute to maintaining our fish and marine bird and mammal populations.

Most of us might never see a forage fish nor would we recognize one if we did, but they are vitally important to maintaining the food web which feeds the more recognizable inhabitants of our marine waters. If you enjoy a meal of wild caught salmon or the sight of basking seals; consider using “soft” armouring techniques to reduce shoreline erosion and bear in mind, on your next walk along a beach, that under your feet could be the developing embryos of these valuable residents of our marine waters.

A group of Metchosin residents, under the guidance of Ramona de Graff, marine biologist and BC’s expert on forage fish, has recently begun sampling along Taylor Beach, to search for evidence of Pacific sand lance eggs (sand lance are known to occur there) and surf smelt spawning. Eventually they hope to expand this initiative along other Metchosin beaches.

References and Resources:

• www.greenshores.ca

• www.coastalgeo.com

• Coastal Fishes of the Pacific Northwest, 1986. by Lamb and Edgell

• Protecting Nearshore Habitat and Functions in Puget Sound: An Interim Guide http://wdfw.wa.gov/hab/nearshore_guidelines/

• http://racerocks.ca/metchosinmarine/foragefish/foragefish.htm

By Moralea Milne for January 2009 Metchosin Muse

Dec 13, 2008

If you take a walk along Taylor Beach you will often see river otters chasing each other through the waves and curious seals stare at you with their velvet painting eyes. Sea birds whirl and alight in the choppy grey sea. These animals provide some visual reference to the surrounding waters but the marine world is not one that is easily accessible to terrestrial creatures such as ourselves.

Just off the beach are large eelgrass beds and seaweed communities that provide crucial nursery habitat for juvenile fish, crabs and octopus. Under our feet as we walk on the beach, Pacific sand lance and (possibly) surf smelts lay their eggs in the high intertidal zone, forgoing their usual aquatic environment during their incubation.

They are known as forage fish, the cornerstone of the nearshore food web that supplies a critical food resource to commercial species such as salmon and cutthroat trout. Seals, sea lions, whales and seabirds, comprise part of the 100 species that are dependant on forage fish for their survival. A 2007 report states that “thirty five percent of the diet of juvenile salmon and sixty percent of the diet of Chinook salmon are comprised of Pacific sand lance”. Because they forage close to the shoreline, coastal cutthroat trout are heavily dependant on sand lance and surf smelts; fifty percent of our endangered humpback whales’ diets are sand lance. Marine birds are also dependant on these fish, there are estimations that seventy five percent of rhinocerous auklet’s food intake and fifty percent of the endangered marbeled murrelet’s diet are comprised of forage fish. Forage fish include Pacific herring, sardines, capelin, eulachon and northern anchovy as well as Pacific sand lance (aka needlefish) and surf smelts.

At night, Pacific sand lance (Ammodytes hexapterus) burrow in the sand as a means of escaping predators, sometimes surprising people walking at low tide along a beach, as they wriggle up from their nighttime “safe houses”. Some people will recognize them from the large, dense schools they form near the surface that are called “bait balls”. They spawn between November and February, more frequently in the late fall. Sand lance use their bodies to form small, shallow pits in sandy beaches, much like salmon redds, in which to deposit their spawn, which will hatch in four to five weeks. Both sand lance and surf smelts spawn during high tides, the upper beach must be covered in shallow water to facilitate egg deposition.

Surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus) can spawn at any time of the year, depending on weather, vegetation and probably many factors of which we are not aware. Surf smelt lay their sticky eggs in the high intertidal zone of a sand and gravel beach, just below the log line, usually between the two lines of deposited seaweed that are readily visible. Pea gravel sized stones, intermixed with coarse sand are preferred spawning material. Surf smelts who spawn in the summer make use of beaches with overhanging vegetation or areas with a continual underground movement of water (such as from a blocked stream slowly seeping through sand and gravel beds). These components ensure the smelt eggs will remain moist and viable under the hot summer conditions. Summer incubation and hatching happen within two weeks while cold winter conditions will increase the incubation time to one to two months. Surf smelt eggs can be found in small patches or they might cover miles of beach, depending on beach conditions and surf smelt abundance.

In order to ensure continued habitat for these important fish, it is important to understand how beaches are formed and maintained.

Bluffs and beaches form a type of unwitting partnership. The bluffs are subject to erosion because of their steepness, the type of material from which they are formed (clay, sand, gravel) and the force of wave action and storm events. Waves are powerful forces that continually act on shoreline materials. They pound against a bluff until it is undercut, when it will fall onto the shore, giving short term protection to the bluff. Slowly, wave action will distribute the fallen material, according to tides, currents and topography. The accumulation of these sediments on beaches and in shallow tidal ecosystems, provides habitat for many different species. Stormwater runoff and removal of bluff vegetation (especially to accommodate the desire for views), can dramatically increase the rate of erosion along bluffs.

Other creatures benefit from this eternal process. Under the cobbles of the low intertidal zone, in the area that is exposed only at low tides (visit the western end of Taylor Beach), you will find small squirming black eel-like creatures known as blennies. There are many species of blennies, some of which will lay their eggs under these cobbles. One or both of the parents will often remain to guard their developing young. At low tides, garter snakes and raccoons will descend from their land based territories and forage for blennies and other marine creatures. If you go searching for blennies, please respect their needs; lift the cobbles carefully and return them to their same positions.

It is not only the changes to rivers through logging activities, overharvesting and pollution from industrial and sewage contamination that has affected our declining marine stocks. Developments along shorelines, where we have not realized the cumulative effects of shoreline changes, have impacted heavily on the ability of marine species to survive. The bluffs to the west of Witty’s Lagoon are continually eroding and supplying sand to Witty’s beach. If you were to “harden” this area by erecting a wall to try to protect those slopes, you would eventually lose the beach.

A consequence of hardening shorelines, by building seawalls and other fortifications, is that the waves will now pound the adjacent shorelines with more force, causing a chain reaction of property owners hardening shorelines; the beaches that remain are scoured by the extra forces working on them and lose the soft sand and gravel that provide surf smelt and sand lance spawning habitat. Less spawning habitat = less forage fish = less food for the 100 species that feed on them.

If you have ever strolled the seawall around Stanley Park, or taken a boat cruise around Victoria’s shoreline, you will soon see that the beaches have been heavily impacted. Many of them have disappeared entirely or the high intertidal zones are gone or have been heavily scoured so that no spawning habitat remains. We are fortunate in that Metchosin has retained much of its forty-five kms of shoreline in relatively natural condition.

There are new “soft” techniques that have been developed to protect shoreline properties. Building natural formations such as sand and gravel berms, planting them with native shoreline grasses and trees, the placement of drift logs, all these mimic the natural barriers to erosion and contribute to maintaining our fish and marine bird and mammal populations.

Most of us might never see a forage fish nor would we recognize one if we did, but they are vitally important to maintaining the food web which feeds the more recognizable inhabitants of our marine waters. If you enjoy a meal of wild caught salmon or the sight of basking seals; consider using “soft” armouring techniques to reduce shoreline erosion and bear in mind, on your next walk along a beach, that under your feet could be the developing embryos of these valuable residents of our marine waters.

A group of Metchosin residents, under the guidance of Ramona de Graff, marine biologist and BC’s expert on forage fish, has recently begun sampling along Taylor Beach, to search for evidence of Pacific sand lance eggs (sand lance are known to occur there) and surf smelt spawning. Eventually they hope to expand this initiative along other Metchosin beaches.

References and Resources:

• www.greenshores.ca

• www.coastalgeo.com

• Coastal Fishes of the Pacific Northwest, 1986. by Lamb and Edgell

• Protecting Nearshore Habitat and Functions in Puget Sound: An Interim Guide http://wdfw.wa.gov/hab/nearshore_guidelines/

• http://racerocks.ca/metchosinmarine/foragefish/foragefish.htm

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)